Even the name, entomophogy, the term for human consumption of insects, doesn’t sound very appetising. A bit of a mouthful. Yet it’s a taste the western world may want to develop.

Insects are already a valued source of nourishment for two billion people. In 80% of the world’s nations, people eat insects – between 1,000 and 2,000 species of them. In parts of Africa and Asia insects are a staple part of the diet. Meanwhile, in the western world, insects are a culinary curiosity, but that is changing. Some UK restaurants, like Mexican chain Wahaca, have been serving up insects in various dishes for a while. And a growing number of start-ups are selling snacks and cooking ingredients based on insects, mainly online.

So far, so niche. Then in November last year, Sainsbury’s became the first national supermarket chain to stock edible bugs. Smoky BBQ Crunchy Roasted Crickets are available in 250 stores across the country. Made by the UK’s Eat Grub, which was set up in 2014, the product is eaten as a snack or a garnish on salads, noodles or tacos. “Insect snacks should no longer be seen as a gimmick or something for a dare,” the Sainsbury’s Head of Future Brands, Rachel Eyre, said at the launch, adding: “it’s clear that consumers are increasingly keen to explore this new sustainable protein source.”

For now, that’s the market – consumers who are adventurous or consciously searching for alternatives to meat-based protein. That may be for reasons of health or out of environmental concern. And they can afford the premium price. In the west, bugfood remains exotic, if not quite a delicacy.

But could insects go mass market?

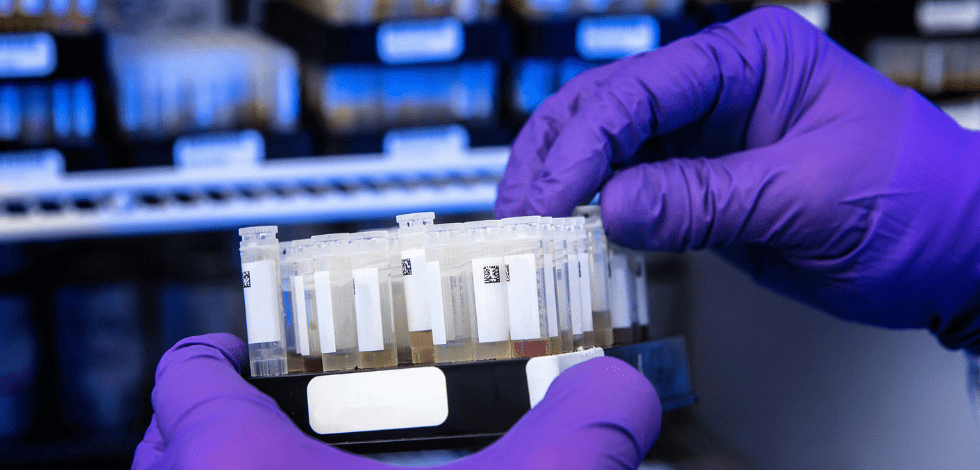

From Australia to the USA, and Germany to China, more than 100 companies are producing their own food brands made from insects, according to a Swedish blog, Bug Burger. And it lists a host of farms, dog food and animal feed businesses, and restaurants into insects, as well. It’s not just small start-ups that have got the bug. America’s Aspire Food Group owns the country’s largest cricket farm, but cannot satisfy demand for cricket flour, its number-one product. Orders are backed up for two years. Aspire is expanding 10-fold with an automated facility – covering 250,000 square feet – in Texas. This will be ‘high-precision farming’.

Aspire has developed sensors using Internet of Things technology to capture real-time data on its insects ‘from hatch to batch’. Data modelling to optimise output and sustainable zero-waste systems are also part of the master plan. Like this swarm of ento-preneurs, many scientists and the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisations believe that farming of insects at scale is inevitable. Three factors add significant weight to this view.

Food scarcity

We are 7.6 billion people. Despite progress in rolling back poverty and hunger, 1 billion of us do not get enough to eat. 400 million are chronically malnourished. By 2020 we will be 8.6 billion. By 2050, nearly 10. Food production needs to increase by 70% to nourish everyone. A disproportionate amount of the world’s land is set aside for beef, pork and chicken production, or growing their feed. A recent study by Cornell University concluded that the food grown exclusively for US livestock could sustain 800 million people; the country’s population is around 320 million. Feeding the world’s growing population will require a radical re-balancing of the global food supply chain.

Foods made from insects, worms and grubs may be rising up the menu. As The Scientist magazine put it: “Eradicating extreme poverty and hunger, and reducing child mortality rates, can be directly addressed by expanding consumption of edible insects.” There is an appetite for change and more ethical eating. Witness the rise of veganism in the UK and Europe, and developments worldwide in synthesising plant-based substitutes for meat. Several factors are at play – healthy eating, superfood fads, animal rights. Climate change looms larger. As its effects hit home, concern could shift heavily to the carbon hoofprint of our food systems.

Climate change and natural resources

The case for farming insects to cut carbon emissions from food production is compelling. According to the UN FAO again, insect farming produces one hundredth of the emissions of the equivalent output from beef cattle or pigs. Figures cited by Eat Grub show that every 1kg of steak is heavily outweighed by its associated greenhouse gases – 2.85kgs worth. The equivalent carbon impacts for pork (1.13kg) and chicken (300 grams) contrast with a measly 1gm per kilo of insect protein. Beef farming is land-intensive, as already mentioned. Climate change will erode the world’s stock of pasture and arable land, even as populations increase. Farming insects would make far more efficient use of what land is left.

Producing 1kg of protein from cattle requires 200 square metres of cultivable land. For pork, the land take is a quarter of that (50m2). A kilo of chicken protein is little better (45m2). The equivalent area for 1kg of insect-based protein is just 15 square metres. The picture is similar for feedstock. Ten kilos of feed go into 1kg of steak. This halves for pork, and again for chicken. For insect protein, the feed input is 1.7kg. Water scarcity will tip the balance further in favour of alternative protein sources. Cows drink around 80 litres a day. (Per 1kg of protein, the water consumption rates for cattle are an astounding 22,000 litres; against 3,500 / 2,300 respectively for pork and chicken, and 1 litre for insects.) Insects are drought-resistant; nor do they require large doses of hormones or antibiotics. (New research confirms some insect species are declining in the wild, due to global warming and insecticides. This should not affect our capacity to farm nutritious varieties.)

Nutritional value

But surely, when it comes to nutrition, meat must out-muscle those pesky little creatures? As you’d expect, the four main insect groups cannot match the nutritional value of our more traditional fare. But that’s not the whole story:

- The protein gap narrows when you look at grams of protein per calorie, (instead of per gram of mass).

- Insects contain more moisture than other animal proteins. Removing this boosts nutritional values significantly.

- The iron in insect proteins is far superior to that of animal meats.

Also, the nutritional profiles of insects differ, as Eat Grub’s founders point out: “Crickets can contain 69% protein and have all essential amino acids. They are high in fibre and vitamin B12, as well as being a great source of iron, calcium and Omega 3 and 6”. Yet there are major challenges. The cost is still very high, artificially so, due to the very low supply. Crickets cost five times the price of chicken. Growing demand and production would turn those economics around. Lab-grown meats and plant-based diets are already growing. However, given the scale of the food supply challenge, the world will need multiple new sources of protein; they can co-exist. The natural simplicity of entomophogy will be an advantage over more tech-driven alternatives. Cultural tastes could be the highest hurdle in the west.

Processing insects in ingredients like Aspire’s cricket flour reduces the yuck factor. Similarly, Eat Grub’s online range not only includes whole insects, farmed in Holland, such as grasshoppers for stir-fries, but also crickets in pizza dough. Bug Foundation in Germany has piggybacked on technical advances in manufacturing veggie burgers. Its Insect Burger is made of buffaloworms and organic soy. EntoMarket in the US takes a radically different approach. Its Bug Love Box, Pizza Superworms and MealWorm Tequila Lollipop dare consumers to be different. But will they buy into this? Analysis by US-based Research and Markets suggests it’s happening. The edible insects market worldwide is predicted to grow 23.8% a year from 2018 to top US$1 billion by 2023.

How will agricultural lobbies respond to upstart rivals? Today’s farming subsidies and protection reflect their immense power. But it’s not inconceivable that runaway global warming could tilt government policy towards entomophogy, especially if public opinion shifts. Bugs could be more than bit players in a food resource revolution. The disruption of the food sector, and innovation in areas such as agri-tech, plant and equipment, land use and production facilities, will be intense, when that reality bites.

#FutureTech

The FutureTech Series explores emerging technologies that are transforming industries, and will impact the way we lead our lives in the future. Using the Timeline of Emerging Science and Technology, developed by Imperial College academics, Ayming UK’s innovation experts discuss the disruptive technologies of the Present, the Probable, and the Possible.

No Comments