Table of contents

Foreword

Our first Innovation Barometer in 2019 cautioned that demand for Research & Development (R&D) was about to surge. We could never have known how accurate those findings would be.

Since the pandemic struck, businesses have faced previously unimaginable adversity. The drastic and rapid changes in social and economic behaviors have forced businesses to adjust their models, both in how they operate and sell. However, it is in this very environment that innovation flourishes. Such fundamental shifts bring both opportunity and risk for all firms. Competition has ramped up, and markets are ripe for disruption. There is no doubt that future sector leaders have been founded during the pandemic, as we can already see start-ups emerging with new, future-facing propositions.

In this report, we take a close look at the state of R&D. What effect has Covid-19 had on innovation processes? What obstacles are keeping businesses from innovating? Has funding dried up, or is it a lack of talent? By comparing this year’s data to last year’s, we uncover these details. Additionally, we have developed a third section specifically to explore sentiments toward disruption, examine whether businesses are keeping up with innovation, and analyze the lessons learned from the pandemic. Businesses have risen to the challenge, but to varying degrees.

The problem is that the pandemic has created a conflicting paradigm wherein innovation is more essential but also more difficult. Those who successfully pivot to new opportunities will flourish, while those who don’t will be left behind. It’s no exaggeration to say that what businesses are doing now is shaping the future.

As we move into the post-Covid economy, innovation will be vital. Not only are economies in desperate need of a boost, but several big challenges lie ahead, such as climate change. However, if there’s one thing innovators do best, it’s solving problems. We must empower businesses and individuals to innovate because, ultimately, we rely on them for solutions.

Fortunately, the pandemic has taught us some valuable lessons. It has reinforced the value of R&D, and businesses can take inspiration from the many successes, such as the development of vaccines, and apply those lessons to enhancing the innovation process. The emergence of new technologies and platforms that facilitate open innovation are also cause for enthusiasm.

All of this, though, depends on funding. Businesses must have access to the necessary funding to ramp up R&D activity. There is a role for us in helping to ensure they have access to all the available funding and are making full use of the significant state funding that is now becoming available.

This report is our biggest and boldest yet, with almost twice as many respondents as last year. We hope you find it a helpful resource for your own innovation efforts.

Section 1 – The innovation landscape

After one of the most turbulent and transformative years in living memory, during which radically innovative goods, services, and inventions played a critical role, attitudes toward innovation have inevitably changed since we published the second International Innovation Barometer in 2020.

There is a growing pressure on organizations to do more, and to do it faster. Short-term growth has become a much more important driver, and public resources and funding are playing a more significant role in this accelerated innovation landscape.

Complexity and confidence

Looking at the numbers in more depth, the percentage of respondents who believe their organization undertakes enough innovation has dropped by 14 points, falling from 85 percent last year to 71 percent this year. Conversely, the share of respondents who feel that not enough innovation is being done has almost doubled, rising from 12 percent to 23 percent.

The number of respondents who believe that innovation is being driven by the increased capabilities of their own R&D teams has also decreased significantly, from 36 percent to 20 percent. Faith in internal R&D is particularly low among the Chemical, Construction, and Civil Engineering sectors.

Part of this apparent loss of confidence can be attributed to timing. In 2020, the data was gathered during a period when many believed that Covid-19 would be a short, albeit dramatic, event. Now, as it has become a more established feature of daily life, there is a growing sense that current prosperity is rather fragile.

“We’ve been speaking about a VUCA world for about 30 years,” says Fabien Mathieu, Partner and Managing Director at Ayming France. “Volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous: really since the end of the Cold War, when some of our more simplistic assumptions and easy alliances swiftly eroded. Today, it’s the climate crisis. Given that the past year has put health risks—both to us as individuals and as societies—under the spotlight, we perhaps shouldn’t be too surprised that confidence in innovation strategies has dropped.

Innovation hotspots

As ever, there are sectoral differences and intra-country contrasts. The sector with the least confidence in its innovative capacities is now health and pharmaceuticals, despite dramatic breakthroughs in vaccine development. Lack of confidence is also most often expressed in Belgium, Spain, and Ireland.

The most confident nation remains the US, alongside the Netherlands. There are inevitably long-term cultural reasons for this: the US has always considered itself the land of opportunity, which perpetuates its belief in being the home of innovation.

It also helps that the US is still riding high on a period of economic momentum that began during the previous administration and appears to have been given a boost by the current administration’s willingness to provide more incentives for ambitious infrastructure projects.

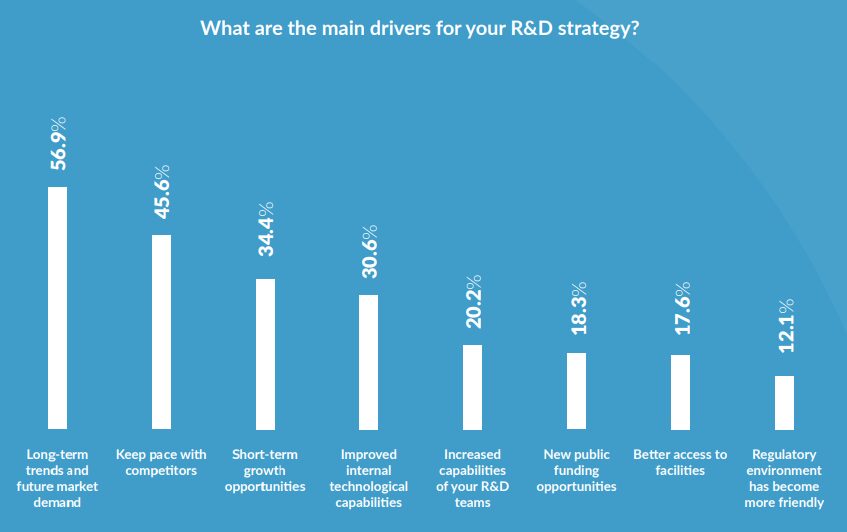

The long and the short of it

As for the drivers of innovation, long-term trends and future market demand remain at the top of the list. In fact, this factor has jumped from 38 percent last year to 57 percent this year, and it rises even further to 72 percent among consumer goods companies. The number of respondents citing keeping pace with competitors as a driver also increased, from 37 percent to 46 percent. Rounding out the top three, short-term growth opportunities are now a driver for 34 percent of respondents—an increase of 13 points, moving from last place to third.

“Innovation strategies have always expressed a duality between short-term and long-term prospects,” says Mathieu.

One is about surviving the current battle. One is about winning the war. The fact that both have increased in influence suggests that businesses are focusing on more sustainable innovation, understanding that current challenges must be overcome to give the business a fighting chance at longevity,

says Mathieu.

Business leaders will therefore need to manage and direct innovation over several timeframes, which will almost certainly increase the demand for more predictability in product and service development. This shift is likely to redefine what is expected of minimum viable products (MVPs).

Insiders and outsiders

When it comes to the resources firms rely on for innovation, the overall picture is one of growing dependence on internal R&D resources, as firms have stuck with the trusted and familiar over the past twelve months. “Internally, you have people who are used to running customer projects to a certain rhythm,” says Olivier Taque, Innovation Project Manager at the engineering services company Bertrandt, based in France. “So while we always want to work with engineering schools and the like, there is a certain reliability and agility that comes with internal resources—something that will have been very important in the past year.”

External private resources, such as R&D from other companies, service providers, or subcontractors, remain the least relied upon. However, the gap between the most and least preferred options has increased again. The share of companies turning to internal resources has grown from 58 percent to 67 percent, while the share using external private resources has decreased dramatically from 47 percent to just 29 percent. This represents a major reversal from the position reported in 2020, when there was a significant jump in the use of external private resources.

However, the number of firms looking to external public resources, such as universities and public research laboratories, for their innovation work has also seen a decline over the past year, albeit less severe—from 42 percent to 35 percent. Additionally, the share of organizations that say their ability to access new public funding opportunities is a key driver of innovation has fallen from 25 percent to 18 percent. These changes can, in part, be attributed to recent alterations in national schemes for R&D tax credits, which have changed the incentives for commercial cooperation of this nature.

The area that has remained most steady—for now—is collaboration or joint ventures with other organizations, with a slight increase from 43 percent last year to 44 percent this year. Collaborations are more frequent in the US and Canada and are most common among Energy and Biotech firms. Conversely, they are least common among consumer goods and manufacturing firms, which tend to rely more on external private resources. This sector contrast is likely driven by the different competitive natures of these industries.

Nonetheless, the amount of collaboration is likely to increase from this point forward. A more collective intelligence will be necessary to tackle the big projects of tomorrow. The challenge will be to harness the possibilities opened up by remote working while overcoming the difficulties it presents in initiating and cementing effective partnerships. Despite these challenges, we can expect a more open approach to building innovative ecosystems, driven by necessity if not by self-interest.

Local vs global

There has been a subtle retraction from internationalism over the past year. Local-only innovation has increased from 42 percent to 47 percent, while international-only innovation has dropped sharply from 11 percent to a mere 2 percent. For those who do choose to innovate internationally, the top destination is the US, followed by Germany and the UK.

Given the pandemic mitigation measures that have made travel more difficult and logistics more challenging, it is perhaps not surprising that firms have looked closer to home for their innovation sites. However, there is also a deeper, more instinctive reason behind this trend: the urge to ‘buy local’ remains strong, and having a local presence is a key strength for many marketing campaigns.

For Olivier Taque, the reasons for local innovation are largely tied to language, culture, and customer expectations.

Innovation is about technique, but it’s also about markets.’’

“Is the market ready at the right time for your preferred innovation? Are customer demands the same in different locations? They progress at different speeds, so there is rarely a universal requirement or demand.”

Despite this variability, the number of firms that combine local with international innovation has increased slightly from 47 percent to 51 percent, maintaining its position as the most popular option. This mixed model is most prominent in the US and Canada, where businesses are also more likely to pursue collaborations to support their innovation efforts.

Follow the talent

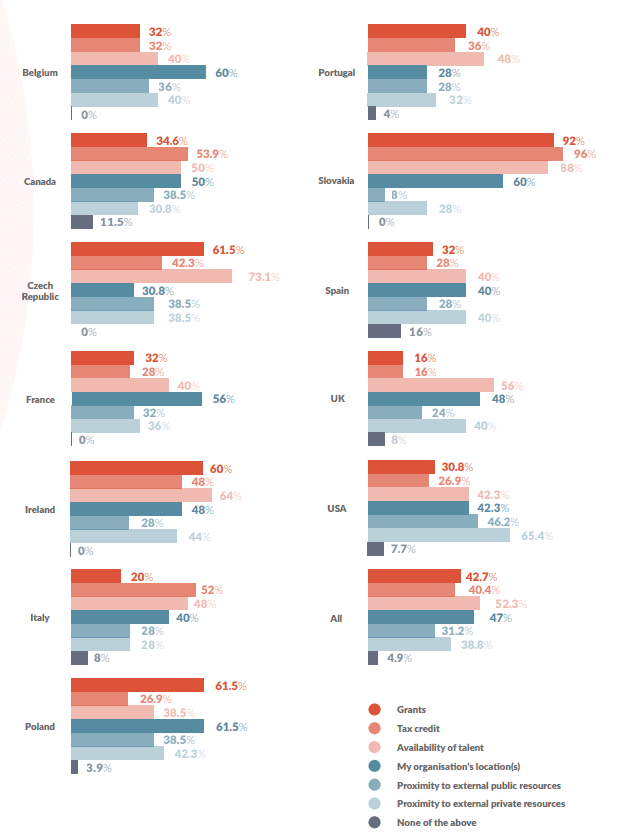

We also asked respondents which factors influence their choice of innovation location. Once again, the availability of talent tops the list and is most likely to influence companies in France and Ireland, as well as those in the Healthcare and Pharmaceutical sectors.

“The way we view talent has shifted over the past year,” says Mathieu. “There’s growing concern surrounding the current cohort of graduates, who have missed out on important aspects of their university education. The pipeline is perhaps not as gold-plated as it once was.”

“Access to talent is obviously a key driver of innovation,” adds Tina Carling, Innovation Director at Morgan Sindall Infrastructure & Innovation.

But the world is changing, and people could well be reassessing their priorities, so companies need to think about how they continue to attract them,” Carling continues. “That could very well come down to a question of location.”

However, this year the availability of tax credits (16 percent) has moved up the rankings and is now ahead of grants (13 percent) as the funding mechanism most likely to influence the location of innovation efforts. “Grant schemes have not necessarily proved their value over the past few years, with success rates lower than expected,” says Mathieu. “Tax credits present less risk to the public purse. With Covid recovery packages coming into play, I expect a more complementary balance between grants and credits to become the norm.”

Key observations

Given the upheaval faced over the past year, it is perhaps not surprising that many businesses have struggled to innovate as much as they would like. This is reflected in the general shape of R&D activity, which has become a more insular affair. Companies are now more likely to depend on their own internal resources for innovation and are slightly less inclined to look to international innovation efforts to drive progress.

As the world begins to open back up over the coming year, we hope to see a reversal of these trends and a resurgence in confidence in R&D teams’ abilities to be real drivers of innovation. Talent will be central to this resurgence, and companies will be closely monitoring the health of the next generation of innovators as they plan their R&D efforts moving forward.

Section 2 – Financing innovation

After a year of extreme uncertainty, it is widely recognized that more innovation is needed to face the next wave of challenges—whatever form they may take. “R&D growth is really driven by the customer base,” says Carling. “All the new contracts are demanding innovation. Government is demanding innovation. They know the old way of doing things isn’t going to get us where we need to be—especially around decarbonisation.”

For that to happen, however, steady and sustainable funding is necessary.

Finding funding

As expected, most innovation remains self-funded. Half of all respondents finance their innovation this way, slightly up from last year. All other forms of funding declined over the past year.

National or regional grants remain the second most common source of R&D funding, chosen by a steady 38 percent of respondents. R&D tax credits are in third place, but there has been a substantial shift in their perceived value. A year ago, 46 percent of respondents saw tax credits as a significant source of funding; that number has now fallen to 34 percent.

“Tax credits are normally counter-cyclical: when the economy shrinks, the appeal of ‘free’ money goes up,” says Mark Smith, Partner R&D Incentives at Ayming UK. “Maybe excessive uncertainty upset the normal rules. But maybe the economic impact of Covid-19 was less severe than anticipated. Substantial amounts of government funds were returned, which adds weight to the latter view.”

Reliance on international (EU) grants has also declined, with only 28 percent of respondents now relying on them, down from 37 percent previously. The recent launch of the €800 billion EU fund could potentially reverse this trend in the near future. However, Olivier Taque adds a note of caution, pointing out that, “It depends on the size of your company. Under EU rules, once you have 500+ employees, your access to EU funds is limited. Local grants, therefore, will still play a major role, even in the single market.”

As for private funding, reliance on equity and debt funding has also decreased. Previously relied on by 33 percent of firms, these sources are now utilized by only 23 percent. The widespread availability of cheap debt from government recovery schemes has not necessarily led to widespread take-up, while greater risk aversion may explain the reluctance to embrace equity funding. Crowdfunding has seen a significant drop, falling from 29 percent to just 7 percent.

“Through the pandemic, people have been spending less and saving more. So, there are untapped retail resources out there—especially in Europe,” says Smith.

The question is more about how best to match those investors with investment opportunities. Crowdfunding is often driven by feel-good factors, like early product access, rather than solid returns. That’s not where people want to put their savings right now.

Asking for advice

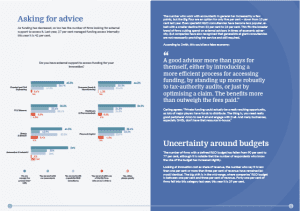

As funding has decreased, so too has the number of firms looking for external support to access it. Last year, 27 per cent managed funding access internally: this year it is 42 per cent.

The number of companies working with accountants in general has increased by a few points, but the Big Four firms are now an option for only five percent of respondents, down from 15 percent last year. One factor contributing to this decline is the recognition that generalists at large consultancies often lack the specific R&D knowledge required.

However, even specialist R&D consultancies have seen a decrease in popularity, with a smaller decline from 33 percent to 26 percent. This reflects a broader trend of firms cutting spending on external advisors during times of economic adversity. Companies have realized that generalists at giant consultancies may not be providing the service and expertise needed.

According to Smith, this could be a false economy:

A good advisor more than pays for themselves, either by introducing a more efficient process for accessing funding, by standing up more robustly to tax authority audits, or simply by optimizing a claim. That’s why the benefits of a specialist adviser more than outweigh the fees paid

Says Smith

Carling agrees: “Private funding could actually be a really exciting opportunity, as lots of major players have funds to distribute. The thing is, you need really good peripheral vision to see it all and engage with it all. And many businesses, especially SMEs, don’t have that resource in-house.”

Uncertainty around budgets

The number of firms with a defined R&D budget has decreased from 90 percent to 77 percent, although it’s notable that the number of respondents who are aware of the size of their budget has increased slightly.

When looking at innovation costs as a share of revenue, the percentages of companies reporting that it is less than one percent or more than three percent of revenue have remained almost identical. The significant shift is in the mid-range, where companies’ R&D budgets fall between one percent and three percent of revenue. Last year, 41 percent of firms were in this category; this year, that number has dropped to 29 percent.

“This is concerning—and a little surprising. Now is not the time to cut R&D budgets. The most successful companies are those that spend more on R&D, and post-pandemic growth will involve investment and even taking some risks,” says Smith. “Cut expenditure too hard now, and you cut your ability to do business—and with it, your ability to bounce back.”

Will those budgets return over the next three years? Fifty-seven percent of respondents say their budget will increase, although the number who expect a significant increase is down five points from last year. The share of respondents expecting a decrease of some kind has also fallen marginally. The slightly bigger shift is among those who simply don’t know, which has risen by four points to 10 percent. Covid-19, climate uncertainty, and a changing regulatory regime in specific sectors appear to be taking their toll on these expectations.

Influencing investment

Regarding the factors that will have a beneficial effect on R&D budgets, technology remains the top influencer, although belief in its positive impact has decreased over the year. Many believe that technology is finally living up to the promises that have been espoused for so long and view it as central to their operations. It is increasingly rare to submit a claim for R&D tax relief that does not involve a technology-related component. Even traditional companies are increasing their investment in technology development, which is crucial for their future.

However, there are some indications that technology has become more “business as usual” rather than an enabler of new development. The number of respondents expecting technology to have no impact at all has increased from 21 percent last year to 25 percent this year.

The potential impact of sector-specific developments on budgets shows a similar pattern. There is a slight but noticeable drop in overall positive sentiment. The percentage of respondents who believe these developments will positively impact their budgets has fallen from 62 percent to 55 percent, while those who believe they will have no impact at all have risen slightly from 27 percent to 30 percent.

Given the funding situation, it is not surprising that the share of respondents who believe funding will have a positive impact has declined, albeit only by a few points. However, because the number who believe it will have a negative impact has increased by a similar margin, there is a decrease in net positivity.

Nonetheless, access to funding has overtaken access to talent as a positive influencer of budget. Less than half now think that access to talent will have a positive impact on budgets, compared to 57 per cent last year. The net positi- vity score (the number who believe it will have a positive impact, less those who believe the opposite) has dramatically fallen from 49 to 34 points.

“Talent is the big one. Most people think that companies innovate. They don’t. People do,” says Carling.

Innovation should be democratised. It’s everyone’s job. So, you need to encourage the culture, and language and behaviours to allow that to happen – and provide the right tools to empower and enable collaboration. But it starts with having the right people.”

Politics and the future

There is better news around (non-Brexit) political risk. Almost half of respondents (49 per cent) believe that political risk will have no impact on their business at all, and the number who believe it will have a negative impact has dropped from 25 per cent to 20 per cent. Nonetheless, the number who think it will have a positive impact has also fallen from 38 per cent to 18 per cent. The number of ‘don’t knows’ is also slightly higher, at 13 per cent.

As for Brexit, it seems to have fallen out of the risk factors: the number who feel it will have no impact has increased from 38 per cent to 56 per cent, while those who feel it will be negative has dropped 14 points from 31 per cent to 17 per cent. The number who believe it will have a positive impact has also fallen, but only by four points.

Finally, there’s the unavoidable impact of Covid-19, which we consider in more detail in the next chapter. Unsurprisingly, most respondents consider it to be a negative impact on their R&D budget. But the number who believe it will have no impact is an encouraging 33 per cent, double the number who think it will be positive.

Key observations

Reflecting the wider innovation landscape, companies have taken a more insular approach to financing innovation over the past year, with a greater dependence on internal sources of funding – and a reduction in the use of external support to access broader sources of budget.

This echoes a reduction in budgetary certainty, with fewer firms reporting de- fined pots set aside for R&D than in the past. That said, there remain reasons for optimism.

Obviously there have been fundamental changes in the economy over the past year. This creates problems but it also creates huge opportunities,” says Smith. “Companies can look to how they exploit these changes, and while there are plenty of indications of uncertainty here, there are also promising signs. The pandemic has not flattened business or its desire to innovate. That is very encouraging.”

Section 3 – Innovation in crisis

Businesses may have run into some challenges this year. Most have faced circumstances that have demanded rapid adaptation. However, it is how businesses have reacted that will determine their future success. History tells us that it’s vital to innovate through a period of significant change.

In this section, we examine sentiments about the sudden changes across the economy, how businesses have reacted, and the lessons they can learn as we emerge out of the crisis.

As Carling says, “It’s made business leaders think ‘hang on a minute, everything could change in a moment, so we need to be more agile. We need to be more flexible.’ Agile was a word that people just used to use without knowing what it meant, and now you really have to practice it.”

Levels of disruption

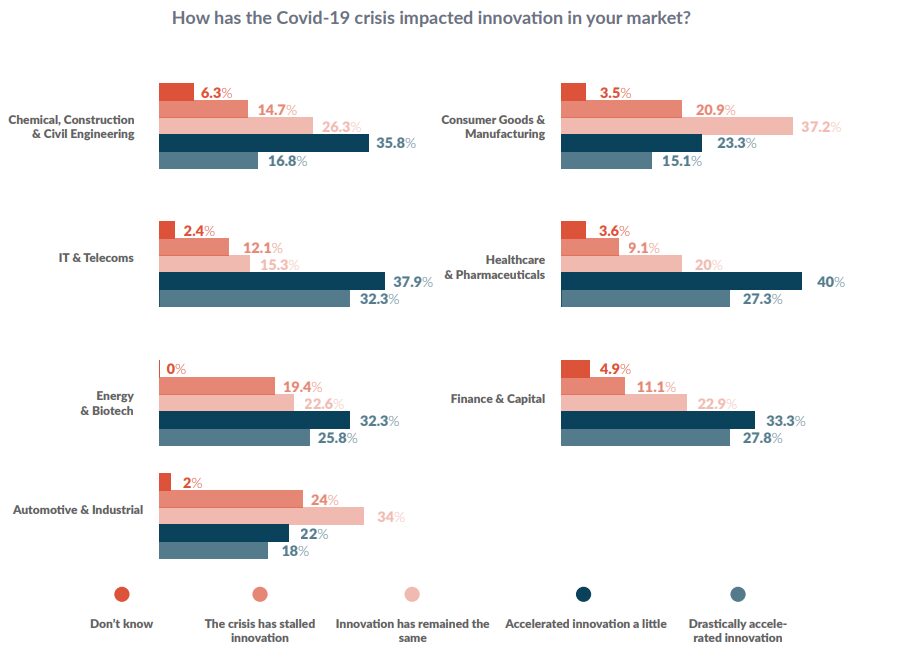

The last year has created the perfect opportunity for disruption. The majority (57 per cent) believe that Covid-19 has accelerated innovation in their market. A quarter of total respondents say this change has been drastic.

There’s been a mixed impact across the economy and the effects have varied sector to sector. Retail, Hospitality and Tourism businesses have obviously been hugely impacted whereas some sectors are thriving.

Among our respondents, IT and Telecoms firms are most likely to believe Co- vid-19 has drastically accelerated innovation in their market. “The pandemic has demanded significant digitalisation,” says Thomas Folsom, Managing Director

at Ayming USA. “When thinking about innovation through the pandemic, that’s what often comes to mind. It’s been key to survival. Both in terms of pivoting selling to online and setting up systems for working at home.”

Fifteen per cent say that the crisis has stalled innovation, led by the Auto- motive and Industrials sectors. In part, this is due to the physical problems of lockdowns. Businesses in this sector depend on a hands-on type of develop- mental process, whereby they develop a tool that needs to be tested. This was delayed when people were at home.

However, Taque suggests, “The main reason here is funding. R&D budgets are calculated on the income of the company, so some have come down drastically. The second part is the human implications of the pandemic. Lockdowns have caused some businesses to furlough staff, which I think has had an impact on confidence. I suspect we will have fewer responses to our internal innovation programme this year because we’ve had 300 people who have not worked for a year-and-a-half, and innovation projects require a certain energy and pragmatism.”

Rising to the challenge

When asked for thoughts on how their businesses had reacted, respondents are generally optimistic. Thirty-six per cent of businesses believe they have innovated a little with minor adjustments, indicating that, while most firms didn’t stop innovating, they also haven’t done anything too ground-breaking.

A quarter of respondents are proud of their reaction and say they have fully adapted to seize Covid-19 opportunities. Finance and Capital firms believe they have innovated most successfully through the crisis. Banks and Fintechs have successfully pivoted to new demands. People have taken up digital banking, trading and payments in record-breaking numbers. “They’re almost technology companies at this point. Most interactions are digital,” says Folsom.

Some companies have focused on keeping the lights on, meaning innovation has taken a back seat. Comfortably the most popular reason for not innovating is that business survival has taken priority, cited by 15 per cent of respondents. But this is exactly the wrong attitude in times like these. We’ve entered a period of disruption and R&D is essential to weathering the storm. If companies fail to keep up in this competitive environment, not only is it a missed opportunity but it is a visible signal they are failing to keep up with tomorrow.

The second biggest obstacle to innovation is sourcing talent, at six per cent. We know there’s a growing talent drought in R&D. Innovation often requires a certain skillset, so the shortage of the right people is driving those responses. What’s more, this problem is likely to worsen.

Smith says, “The talent pipeline is a concern. We’ve had a series of graduates completing degrees remotely. Are they getting the same quality education? It’s also understandable to see why students question the value and some might not bother altogether. Companies need to be mindful of this pipeline and adapt to attract the best people. For example, people are reassessing their priorities, and many are demanding flexible working.”

Surprisingly, people did not cite remote working as a barrier to innovation. Folsom says, “Perhaps they are underestimating the impact of remote working. A mechanical engineer that’s trying to build a new widget couldn’t work with his team to put the widget together and test it. But there’s more to this. Innovation often stems from human interaction. It’s often face-to-face spontaneous interaction that sparks ideas and gets people innovating.”

Staying in the race

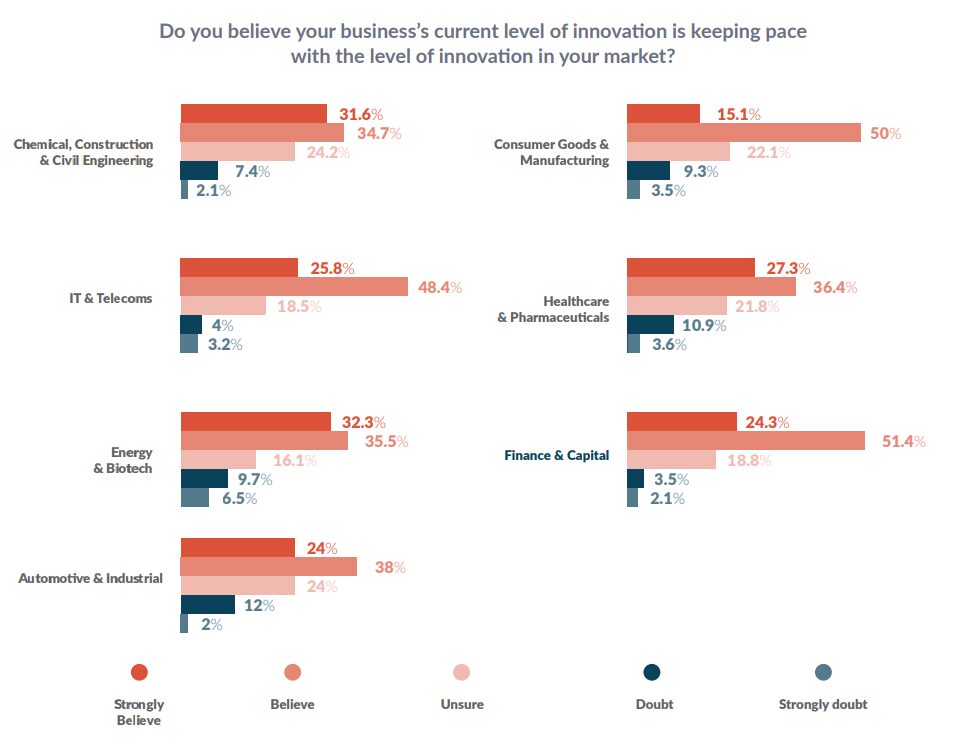

We wanted to see how our respondents felt about their innovation. Most res- pondents (69 per cent) believe they are innovating enough to keep pace with the changes in their market, with a quarter of respondents saying they strongly believe this. Finance and Capital are most likely to believe they are keeping pace with innovation – in line with the success story of this sector.

While positive, this presents a danger of complacency. The media narrative is one of doom and gloom, meaning those businesses surviving feel like they are doing well. But businesses must be wary of disruption. They may not be fully aware of the innovation that is due to come to market, both from peers and startups.

Folsom says, “This race isn’t out in the open. People don’t know what their competitors are up to. They’re swinging the bat half-heartedly because they’re hearing about others having problems. But they might be sleepwalking into a problem. Only time will tell.”

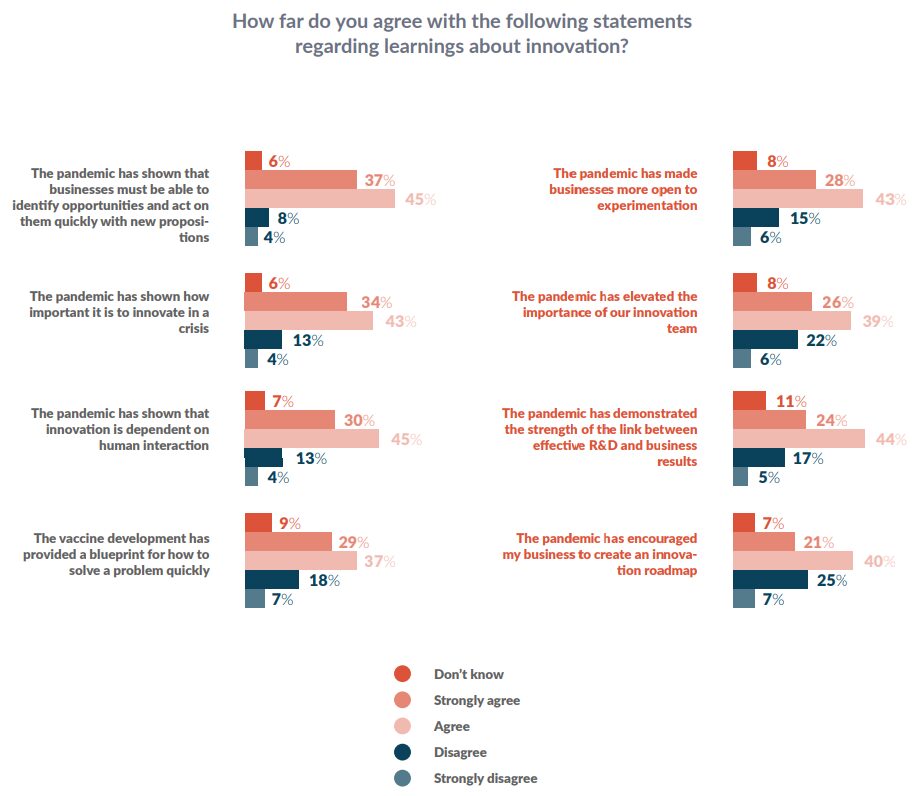

Our respondents have some noteworthy reflections on the pandemic. General- ly, the results are positive, and the respondents have agreed with most of the statements to varying degrees. What is interesting here is which statements have come out on top.

At 82 per cent, the statement most commonly agreed with was that the pandemic had shown that businesses must be able to identify and react to opportunities. If businesses embrace and take forward a reactive mindset, that is a valuable and positive learning. Unsurprisingly, this sentiment is felt most strongly among the Healthcare & Pharmaceutical sector – almost certainly due to the success of those who have developed vaccines.

The second most agreed with statement is that businesses must innovate in a crisis, with 76 per cent agreeing. This is certainly an important learning from the crisis. However, although most agree, 17 per cent of people do not believe it’s important to innovate during a crisis, which is alarming. Businesses that fail to realise the importance of innovating during a crisis are really setting themselves up to struggle.

There are some other surprises in the research. The least agreed with response was that the pandemic had encouraged respondent’s business to create an innovation roadmap, with 37 per cent disagreeing. One would hope that this is because these com- panies already have a roadmap. If they don’t have one, it is essential they put one in place.

The opinions of Automotive and Industrials res- pondents are an outlier here. These firms are least likely to believe that Covid has elevated the im- portance of their R&D team and are least likely to have set up an innovation roadmap. Taque says, “The R&D objectives of car companies haven’t changed much at the hands of the pandemic. We are mainly driven by what Europe decides regar- ding emission rules, or the kinds of cars and fuel we can use. But everything changes every year, and you have new rules. It’s really difficult to know where exactly to invest but it’s generally targeted towards electric vehicles.”

As for the vaccine, two-thirds of people say that the development of a vaccine has provided them with a blueprint from which to think about how they might solve problems more quickly – a lower statistic than expected. This idea is not to be ignored.

As Smith says, “The one big thing for the last year for me is looking at what we can do if we have a coordinated response. We can identify a novel disease and develop a vaccine in a very short space of time if we are focused on it.

“We face a lot of big challenges as a globe and we should realise that we’ve got it within our power to solve these challenges and solve them much, much quicker than people would think. Challenges like the climate crisis are solvable with innovation, but we need to spend the money, we need to be targeted, we need to be co-ordinated.”

Key observations

If anything, the pandemic has proved that necessity is indeed the mother of invention. Already, we have seen the emergence of pandemic-induced innova- tion, and there is surely plenty more in development. It’s clear that businesses are thinking differently and that’s going to lead to positive change.

The crisis is something that we’re going to have to watch and learn from. Unfortunately, we’ll never know when there’s going to be another Covid-19.

What we can do is be bold in our ambitions.

Innovation is trickling down the supply chain – Olivier Taque, Bertrandt

“Automotive R&D is typically driven by efforts to become more environmentally friendly, particularly by moving away from gasoline engines towards fully electric vehicles. This shift often requires the development of new parts, resources, and raw materials.

A significant question emerging in this context is: who holds the responsibility to innovate? As a supplier, you might be best positioned to make a product more sustainable or lighter. However, this means businesses are increasingly asking their suppliers to innovate on their behalf, effectively shifting the responsibility—and the associated cost—of the R&D effort onto the supplier. This is a relatively new phenomenon.

In our business, we were traditionally focused on the “D” in R&D. A client would come to us with an idea and ask us to develop a specific tool or part that they might not want to develop internally. Now, we find ourselves having to research and propose solutions based on their projected needs, shifting more towards the “R” in R&D.

The responsibility to build knowledge is being outsourced. This shift might actually be beneficial. It has led us to make new discoveries, both with our own materials and test systems, as well as through collaborations with our customers.”

Re-thinking the creative process – Tim Carling, Morgan Sindall

”

Brainstorming, as a creative concept, is flawed. It was invented in the ’70s by an ad man, but it doesn’t always foster the best environment for creativity. While dissent, debate, and discussion are essential for innovation, there’s a time and place for them. Not every idea is a good idea, and in a brainstorming session, the linear thinking of some participants, particularly engineers, can stifle creativity. You don’t want someone dampening the mood by saying, “Oh, that won’t work” or “That’s too ambitious.” Such environments can be intimidating for introverted individuals and detrimental to cognitive diversity.

To truly stimulate creativity, you need to provide the right tools. We’re using a platform called MURAL for collaborative workshops. It’s a highly creative space where you have unlimited pens, post-it notes, and whiteboards. Platforms like this are becoming increasingly important in the innovation process.

The best way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas, and the best way to generate lots of ideas is to involve many people. If you only have two engineers brainstorming in a room, you’re limited to their ideas. It’s much more effective to have a system that enables open innovation. This is the approach many are now adopting: you can post your challenge online and ask the world, “This is our problem, does anyone have an answer?”

That’s the future of innovation.”

Executive summary

- Confidence Down on Last Year: The impact of the pandemic has led to a decline in the proportion of respondents who feel their organization undertakes enough innovation, dropping from 85 percent to 71 percent.

- Long-Term Planning: While short-term priorities have become more significant, long-term trends and future market demand remain the biggest drivers of innovation. This factor was selected by 57 percent of respondents, a significant increase from 38 percent last year.

- Boosting the Budget: Firms are increasingly managing access to funding internally, with 42 percent of respondents now preferring this method, up from 27 percent last year. Meanwhile, reliance on the Big Four and specialist consultancies has decreased as businesses have sought to cut spending on external advisors.

- Uncertainty Around Budgets: Having a defined R&D budget is less common this year, dropping from 90 percent to 77 percent. While 57 percent of businesses are expecting budget increases, the percentage of those who are uncertain has risen, with one in ten respondents now unsure about their budget outlook.

- Jump in internal resources: The percentage of companies who have kept innovation in- house is up from 58 per cent to 67 per cent, driven by a desire for increased reliability, simplicity and speed. External private resources have decreased dramatically from 47 per cent to just 29 per cent.

- Keeping things close to home: Pandemic-induced logistical challenges have shrunk international-only innovation from 11 per cent to only two per cent while local-only innovation is up from 42 per cent to 47 per cent.

- A new pace of innovation: Fifty-seven per cent believe that Covid-19 has accelerated innovation in their market, with a quarter of total respondents saying this change has been drastic. However, 15 per cent say it has stalled innovation, which often depends on the sector.

- Reacting to the pandemic: Thirty-six per cent say they have innovated a little, whereas 25 per cent say they have fully adapted to seize Covid-19 opportunities. In terms of obstacles, the most popular reason for not innovating is that survival took priority, cited by 15 per cent of respondents.

- In Search of Talent: The biggest factor influencing the location of business innovation is the availability of talent, cited by 26 percent of respondents. While demand for R&D has surged, there is a dwindling supply of skilled people to meet that demand.

- Troubles with Funding: Aside from internal funding, all other forms of funding have seen a decline. R&D tax credits have experienced a substantial drop, with only 34 percent of respondents using them this year compared to 46 percent last year. Equity/debt funding and crowdfunding have also decreased, with usage down by 10 percent and 22 percent, respectively.

- Is It Enough? Sixty-nine percent of respondents believe their businesses are innovating enough to keep up with changes in their market, which may suggest some complacency. Businesses must remain vigilant about competitor innovation and be cautious of potential disruption.

- Reflections on the Pandemic: A significant 82 percent of respondents agree that the biggest lesson learned during the pandemic is the importance of a business’s ability to identify and react to opportunities. On the other hand, the pandemic has been less effective in encouraging the creation of an innovation roadmap, with 37 percent of respondents disagreeing that it has prompted them to develop such a plan.

Methodology

This report, our third annual International Innovation Barometer, continues our research and analysis of R&D from the past two years. For this edition, we surveyed 585 senior R&D professionals, Chief Financial Officers, Chief Executive Officers, and business owners. Thirteen percent of the total respondents were representatives of Ayming clients.

Our findings are divided into three sections, each analyzing specific areas. As in previous editions, the first two chapters focus on the innovation landscape and financing. This year, our third section delves into innovation in a crisis, exploring the reactions to and lessons learned from Covid-19. The questions for the first two sections have remained consistent with last year’s survey, allowing us to draw year-on-year comparisons and identify trends.

These findings have been analyzed by three members of Ayming’s senior management, along with insights from two external contributors. These contributors include: [details to be included in the full report.